ANTITEXT

The Antitext exhibition deals with the problem of absence. Are we influenced by what we don't know? Or is our cultural memory formed exclusively from the texts we have read, studied, and re-read?

:

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

“Antitexst” is in Kharkiv, Ukraine (Kharkiv Literary Museum, February 2024)

“Antitexst” is in Kharkiv, Ukraine (Kharkiv Literary Museum, February 2024)Partners:

DVORNIKOV_DESIGN Studio

Design: GRAFPROM studio

Translation into English: Iaroslava Strikha

Translation into German: Sofiia Onufriv

The exhibition was held:

“Antitexst” is in Lviv, Ukraine (The National Museum-Memorial of Victims of the Occupation Regimes, May-October 2023)

“Antitexst” is in Lviv, Ukraine (The National Museum-Memorial of Victims of the Occupation Regimes, May-October 2023)- The National Museum-Memorial of Victims of the Occupation Regimes (May-October 2023, the Prison on Łącki Street, Lviv, Ukraine);

- Kharkiv Literary Museum (February-April 2024, Kharkiv, Ukraine);

- The “Kharkiv: (Non-)Relocated Culture” festival at the Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theater in Ivano-Frankivsk (September 2024, Ukraine);

- The art space of Hotel Continental – Art Space in Exile (October 2024, Berlin, Germany, the exhibition’s German-language version);

- German-Ukrainian festival IMMER WIEDER AUFBRUCH (October 2024, Cologne, Germany, the exhibition’s German-language version);

- The annual conference and general assembly of the Austrian Association of Slavists at Graz University (November 2024, Graz, Austria, the exhibition’s German-language version);

- With financial support from Michael Zeller and Lion's Club of Wuppertal, Sofija Onufriv and Translit Translators’ Union, Plarium Ukraine, Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund, Yuriy Andrukhovych;

- The exhibition’s German-language version was created and exhibited (in Berlin and Cologne, Germany) with financial support from Transformation Communications Activity (TCA) project financed by USAID and information support from Ukrainian Institute.

Curators` text

“Antitexst” is in Berlin, Germany (The art space of Hotel Continental – Art Space in Exile, October 2024)

“Antitexst” is in Berlin, Germany (The art space of Hotel Continental – Art Space in Exile, October 2024)

When a foreign culture is being imposed as dominant, the texts that don’t fit its confines become “antitexts” and are marked for destruction. This leads to the loss of cultural memory enshrined in these texts.

In the Soviet era, the Ukrainian cultural legacy that did not fit the official doctrine existed “in hiding.” The Soviet authorities destroyed those texts or hid them in special collections where they remained inaccessible to the broad public, persecuted their authors and punished readers for the very fact of being familiar with these texts. Because the Soviet authorities used literature exclusively as a propaganda tool, and the declared “internationalism” hid a rigid Russification.

Those who dared to preserve these texts had to hide them too if they wanted to have a chance to hand this cultural legacy over to subsequent generations.

So, hiding could have two diametrically opposed goals:

1. To hide Ukrainian culture in order to destroy it.

1. To hide Ukrainian culture in order to preserve it.

In the struggle between black and white, there’s always room for some mixing of colors, and that is the space of decision-making. The space of responsibility.

Michael Zeller is on the opening “Antitext” in Colongne, Germany (German-Ukrainian festival IMMER WIEDER AUFBRUCH, October 2024)

Michael Zeller is on the opening “Antitext” in Colongne, Germany (German-Ukrainian festival IMMER WIEDER AUFBRUCH, October 2024)In Ukraine, the 20th century, much like the 21st, began with the battle for the survival of the nation and its right to self-identification. It is rather symptomatic that we are still facing the same enemy a century later, which is evidence not just of the pervasiveness of their imperial ideas, but also of our memory blanks.

Isn`t that why the world knew about Ukraine exclusively through the prism of Russia? A whole layer of Ukrainian literary and historical texts was destroyed in the twentieth century. This texts could have shaped our narratives, through which we could have spoken to the world.

“Antitexst” is in Graz, Austria (The annual conference and general assembly of the Austrian Association of Slavists at Graz University, November 2024)

“Antitexst” is in Graz, Austria (The annual conference and general assembly of the Austrian Association of Slavists at Graz University, November 2024)The goal of the exhibition is to show how the Ukrainian cultural memory was manifested over the last century, ensuring “remembrance” after complete “forgetting,” and how present-day Ukrainians address certain meanings while their material embodiments remain physically hidden to protect them from yet another Russian imperial attack.

The exhibition does not include museum pieces. Instead, there will be constructions with texts about them. Thus, we would like to emphasize that Ukrainian cultural heritage is under a threat now, museums evacuate or conserve their collections in the basements. There are cases of both destruction of museum buildings by russian weapons and plundering museums` collections by russian troops in temporarily occupied territories.

The collection of the Kharkiv Literary Museum includes many such antitexts from the Soviet period. The most valuable museum objects were prepared for evacuation and relocated to safer places at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. As the result, today we are hiding artifacts from the threat, though we thought, they had survived their most difficult times already.

What did people put in their emergency bags when fleeing the war?

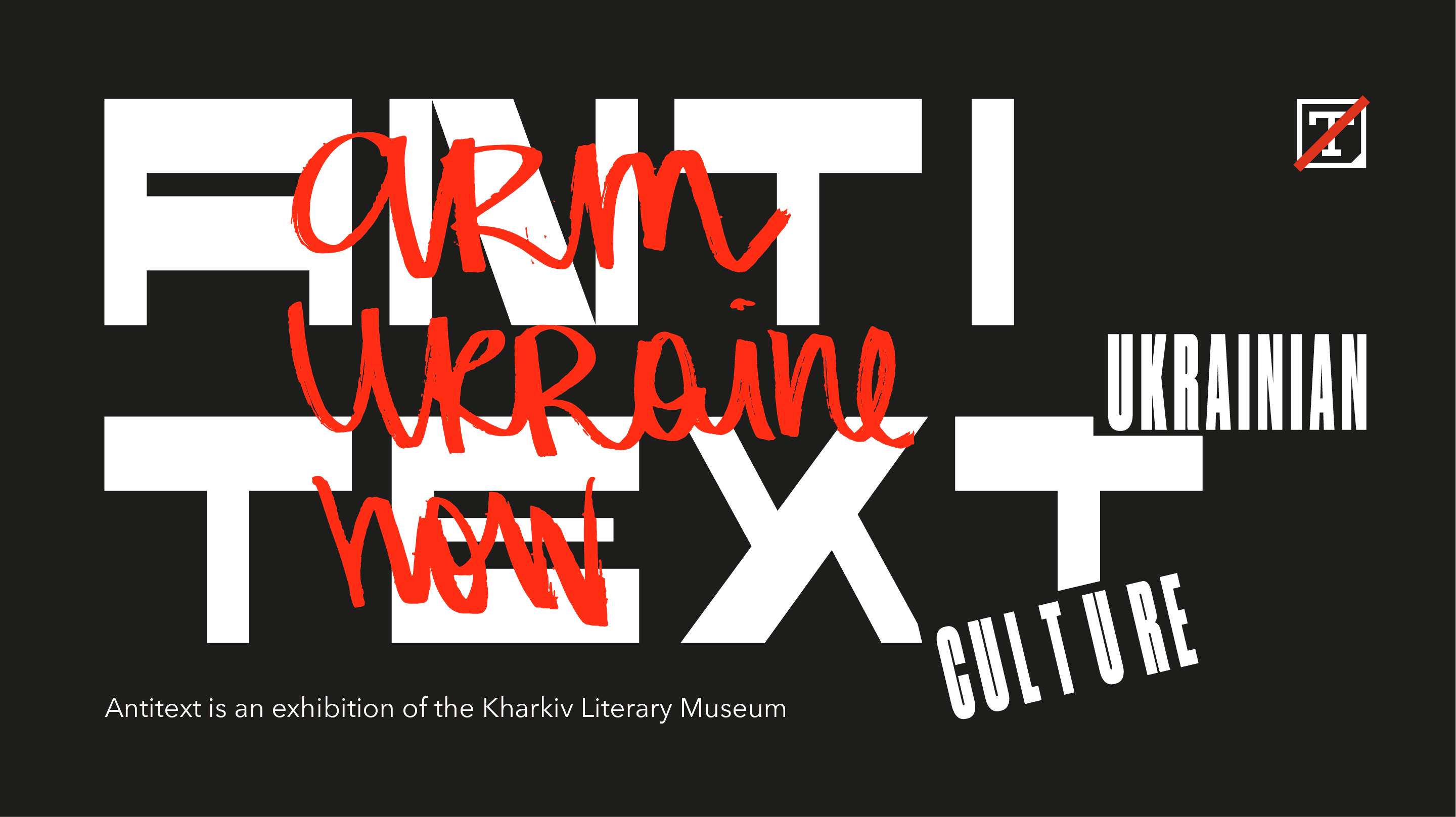

A note by Maria Pylynska asking to preserve I. Dniprovsky's archive, which was in a suitcase with documents (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

A note by Maria Pylynska asking to preserve I. Dniprovsky's archive, which was in a suitcase with documents (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

During WW II, Maria Pylynska, a translator and linguist, packed up the most precious part of her husband’s archive and always took the suitcase with her whenever she had to go down to the bomb shelter. Her husband was Ivan Dniprovsky, a writer of the Red Renaissance era.

Dniprovsky died of an illness on December 1, 1934, which meant that his manuscripts, letters and documents were not confiscated after arrests or destroyed by the Soviet authorities. In a letter to his wife, the writer asked her to destroy his archive after his death: “[...] Don’t publish any part of my manuscripts then, just burn it all. I don’t want these drafts and notes to be known as ‘my legacy.’ ... Not a single unpublished line should emerge into the world. You are my friend, and so you will do it... then” (1927, an artifact from the museum collection, now hidden).

Nevertheless, Maria Pylynska ignored her husband’s request, even though preserving the letters and photos of writers persecuted during the Stalinist terror was dangerous.

In the 1990s, Pylynska’s son from her second marriage, who for the longest time did not know what treasures remained hidden in his apartment in the Word Writers’ House, donated the archive to the collection of the Kharkiv Museum of Literature.

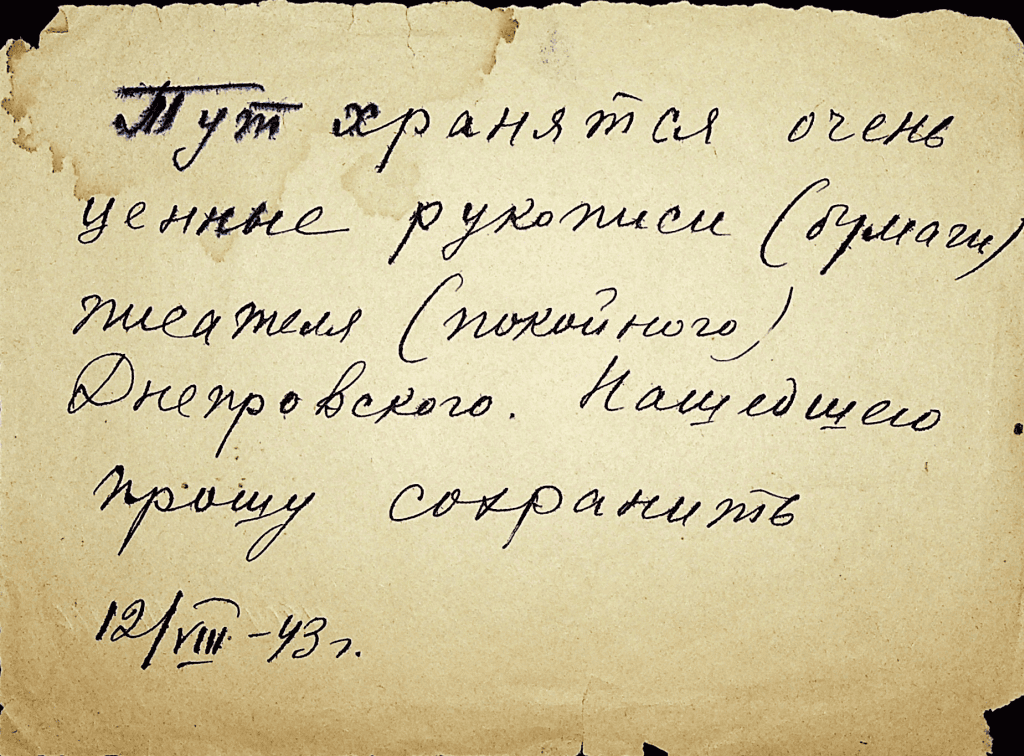

Khotkevych’s Return

One of Hnat Khotkevych's books, inherited to the Kharkiv Literary Museum by the will of his daughter from France.

One of Hnat Khotkevych's books, inherited to the Kharkiv Literary Museum by the will of his daughter from France.

Hnat Khotkevych was a writer, literary scholar, art scholar, bandura player, composer, historian, ethnographer, theatrical and musical worker and teacher. He was a ubiquitous figure, traveling from the Slobozhanshchyna region around Kharkiv in the east to Lviv in the west. He is one of the figures whose lost heritage is emerging out of hiding slowly and fragmentarily.

During the Stalinist terror, a criminal case was fabricated against him. He was arrested on false charges of espionage and belonging to a counterrevolutionary organization. According to the protocol of a session of the Special Troika of the Ukrainian NKVD in the Kharkiv Region of September 29, 1938, Khotkevych was sentenced to death; his personal belongings were to be confiscated. Despite that, his family managed to not just save his archive from confiscation, but also to take it to forced emigration. A part of the archive had to be left in Ukraine for storage in a museum.

After Hnat Khotkevych’s daughter, Halyna, first visited Kharkiv, the Kharkiv Museum of Literature received several objects from his archive that had been taken abroad. After Halyna’s death, the museum inherited several of Khotkevych’s lifetime editions.

At present, the Museum of Literature manages Khotkevych’s mansion in the village of Vysoky, Kharkiv Region, and a small part of his archive in its collection, now hidden.

“My mother and me took the major part of his archive to the central museum, where it remained under the label of ‘do not touch’ up until the late 1950s. Khotkevych’s personal effects, drawings and banduras travelled on with us in our suitcases.” (Halyna Khotkevych, Where Grass Doesn’t Prickle [Там, де не колеться трава], Lviv, 2017)

Samizdat (Samvydav): without censorship

Microtext. Articles by Yuriy Badzio. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Microtext. Articles by Yuriy Badzio. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Samizdat encompasses the practice of self-publishing and distributing uncensored texts. Samizdat in Ukraine was most widespread in the 1960s-1980s, when Ukrainians fought for their national, political and civic rights in the USSR. Literary works by Vasyl Symonenko, Vasyl Stus, Lina Kostenko, Iryna and Ihor Kalynets, polemical essays by Ivan Dziuba, Yevhen Sverstiuk, Ivan Svitlychny, Viacheslav Chornovil, Myroslav Marynovych and others were all distributed in handwritten or machine-typed copies, photographs and negatives, or as tapes. As anti-Soviet resistance evolved, self-published human rights journals and digests became its de facto infrastructure.

One could receive a lengthy prison term for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda” for storing, manufacturing or distributing samizdat. Despite the authorities’ concerted efforts “To prevent illegal distribution of anti-Soviet and other pernicious materials,” samizdat remained the main source of truthful information about the state of Ukrainian culture and human rights. It has had a major effect on the public opinion on the eve of the USSR’s collapse.

There are artifacts of samizdat in the museum collection, now hidden.

Special funds: libraries without readers

Book depositories and structural subdivisions of libraries that stored publications banned from free circulation by the Soviet censorship were known as special storage funds and divisions. Similar units existed in archives and museums.

Established in 1921, special funds were not liquidated until 1990.

Publications ended up in special funds after libraries and bookstores were inspected for banned editions based on lists issued by the Main Directorate for Literature and Publishing Houses. Any publications that contradicted the Marxist-Leninist ideology were deemed “pernicious,” as did all books published in Western Ukraine before 1939, during the Nazi occupation and in the diaspora, as well as books containing mentions of persecuted figures and facts “uncomfortable” for the Bolshevik authorities.

Special funds staff was vetted and selected by the state security apparatus. Only certain categories of library users could get access to special funds after following a complicated application procedure: scholars, graduate students, party committee members of various levels, engineers, journalists, official counter-propaganda workers. Any potential user was to file a precise request because these books were not listed in general catalogues, and special fund catalogues was only accessible to the staff.

During the Khrushchev thaw, criminal cases from the era of Stalin’s personality cult were reviewed. Hundreds of thousands of wrongly convicted prisoners, including artists, were rehabilitated. Publications connected to the rehabilitated figures were moved from special funds to the main library holdings. The list of authors whose works were to be removed from circulation was whittled down by 2,535 names by January 1, 1960, from the initial total number of 3,310. 18,000 titles returned to general circulation.

The next large-scale opening up of special funds fell on the perestroika period (1985-1991), despite the Main Directorate taking every step to slow down the process.

Despite their main function of “a prison for books,” special funds have played an important role as a place where banned texts were preserved. The surviving 2-3 copies of banned books or magazines were kept in special funds while any other remaining copies were destroyed. Many Ukrainian titles from the 20th century now exist in less than 10 copies.

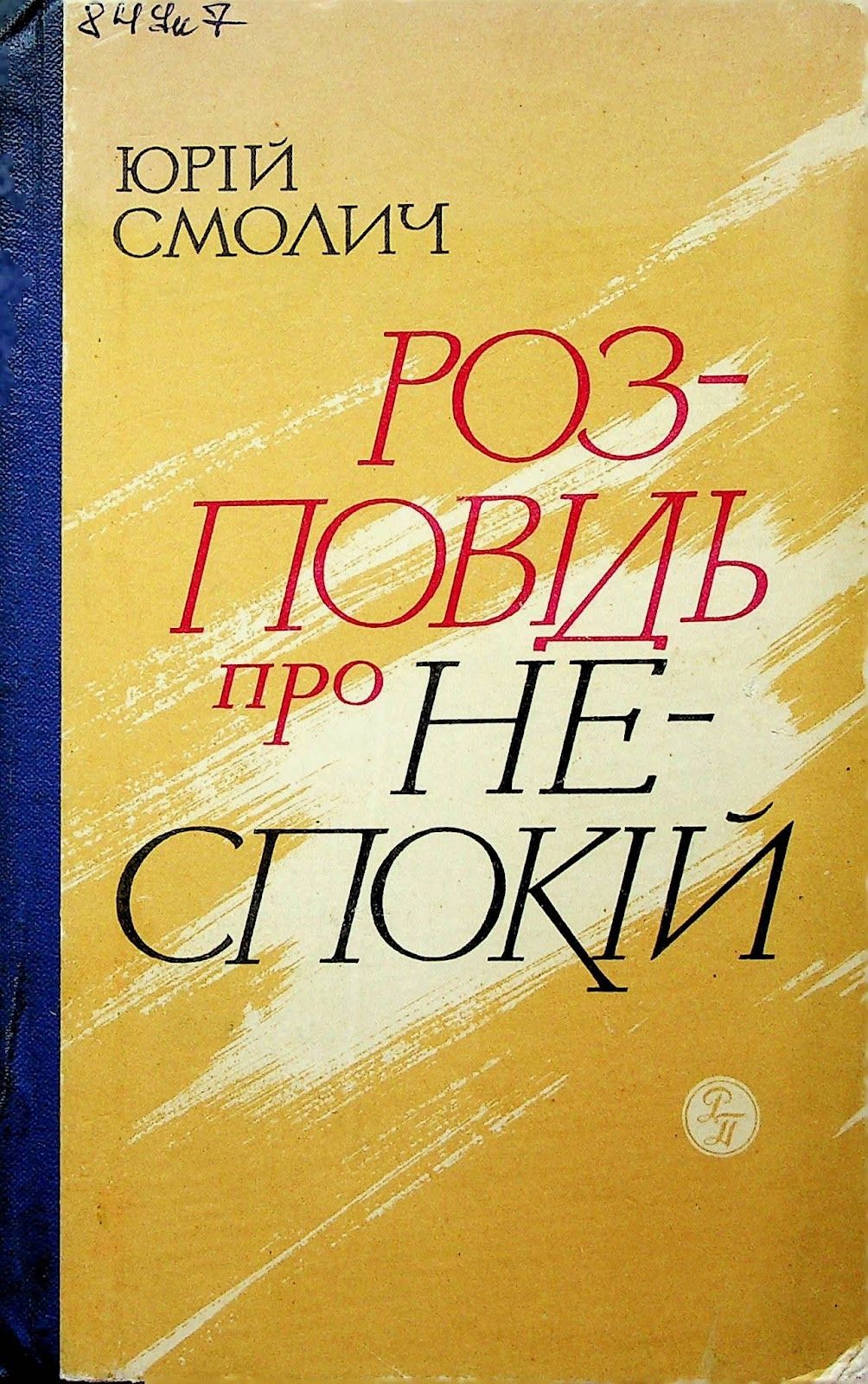

Yurii Smolych’s censored memoirs

Yurii Smolych. The Tale of Unrest. Kyiv, 1968. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Yurii Smolych. The Tale of Unrest. Kyiv, 1968. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

In the 1920s, the Ukrainian writer Yurii Smolych was a member of Soviet Ukraine-centric literary organizations Hart, VAPLITE and Techno-Art Group A. In the mid-1930s, he “volunteered” to become the NKVD’s secret informer, collaborating with the USSR’s political repressive apparatus. That was Smolych’s trajectory: starting out as a member of VAPLITE, a literary organization that was in opposition to Moscow (along with leading Ukrainian writers Mykola Khvyliovy, Maik Yohansen, Mykola Kulish and Mykhailo Yalovy), he eventually became the NKVD’s informer.

Aside from his fiction, Yurii Smolych left three volumes of memoirs about the literary process and writers of the 1920s. Despite holding leading posts in the Union of Writers, it took him several years to get these books published. The authorities resisted the publication because the memoirs dealt with repressed writers. Yurii Smolych did not describe the Great Terror as such, but the names mentioned there sufficed to get the censors on edge.

The Tale of Unrest (1968), The Tale of Unrest Continues (1969) and The Tale of Unrest Has No End (1972) had for a long time remained the only works in the USSR to have mentioned the life and works of the 1920s generation of writers.

There are relevant artifacts in the museum collection, now hidden.

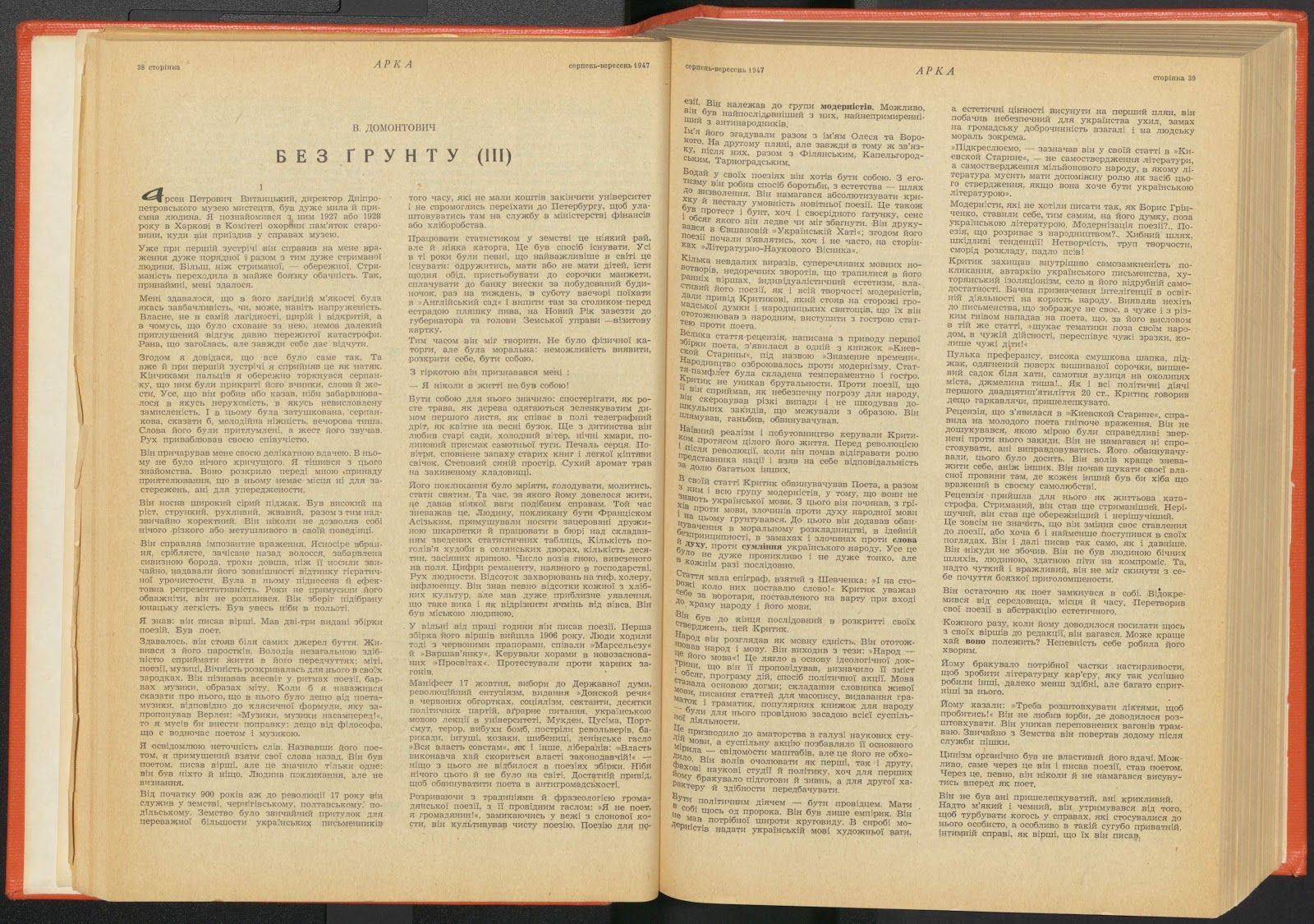

Viktor Petrov/Domontovych/Ber

Victor Domontovych. On Shaky Ground. The page from “Arka (Arch)” magazine, v. 2 - 3, Munich, 1947 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Victor Domontovych. On Shaky Ground. The page from “Arka (Arch)” magazine, v. 2 - 3, Munich, 1947 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Viktor Petrov was a modernist writer and also a Soviet agent who edited a Ukrainian Kharkiv-based publication Ukraiinsky Zasiv during the Nazi occupation in 1942-43 (we have a copy in the museum collection of the Kharkiv Museum of Literature, now hidden). He later ended up in the Ukrainian intellectual émigré milieu in Germany, where he penned a long essay not just mentioning the banned names and works of repressed Ukrainian intellectuals, but also describing terror as a method of state governance in the USSR. His work Ukrainian Intelligentsia, the Victim of the Bolshevik Terror was published in Germany in 1955-56. Petrov himself disappeared from Germany several years previously under mysterious circumstances before equally mysteriously resurfacing in the USSR.

Was he the founder of the genre of an intellectual novel in Ukrainian literature, a conscientious scholar with innovative views, a Chekist informer, a Nazi collaborator, or a man of many facets? He was one of many who were forced to make tough choices during that era of tumultuous historic changes.

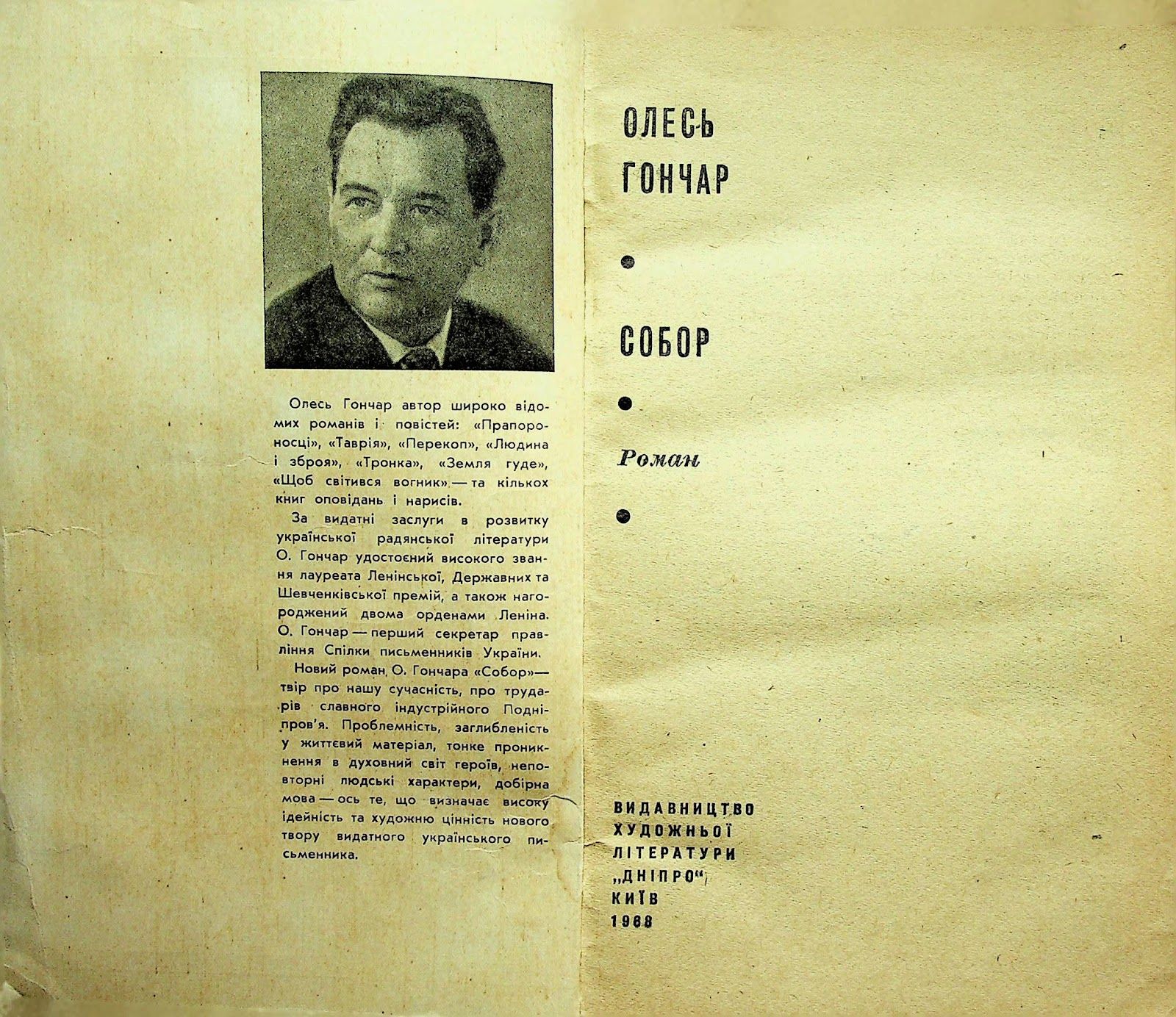

Oles Honchar: Punished with Awards

Oles Honchar. Cathedral. Kyiv, 1968 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Oles Honchar. Cathedral. Kyiv, 1968 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

In the early 1968, a new novel by the Ukrainian writer Oles Honchar, decorated with high offices as well as Stalin and Lenin Prizes, came out. Cathedral was a warning about the society’s moral degradation and historic memory, about spirituality and humanity. The writer immediately became the target of a smear campaign orchestrated by the Soviet authorities, first by “expert” party functionaries, and then by their “tamed” literary scholars. At the same time, he kept receiving heartfelt support from grateful readers, albeit in private. The situation mirrored the events of the novel.

Due to his authority as a writer, Oles Honchar didn’t lose his freedom or even his high posts. He survived the tough period of the witch-hunt and refused to publically “repent for his mistakes,” as was customary during the Soviet period. The authorities tamed the writer again, plying him with status symbols, but Cathedral would not be republished until two decades later. Access to the first publication was severely limited.

The 1968 edition of the novel is in the museum collection, now hidden.

Volodymyr Sosiura (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Volodymyr Sosiura (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)The famous Soviet Ukrainian poet Volodymyr Sosiura (1898–1965) wrote his poem "Love Ukraine" in 1944. The deeply patriotic tone of the poem posed a challenge to the Soviet censors from the very beginning. In a couple of years, after World War II ended, the government launched a campaign of persecution against the artists who deviated from the party line in their works. As a result, many Ukrainian research institutes focusing on the history and literature of Ukraine, artists' unions, newspapers and magazines as well as prominent cultural figures, including but not limited to writers, composers and directors, found themselves targets of devastating criticism. Sosiura was targeted for his poem "Love Ukraine." The poet rewrote his work, changing the line "Without her [Ukraine], we are nothing but dust and smoke" to "In the brotherhood of nations, she shines over centuries". The Soviet ideological machine no longer deemed it possible to treasure Ukraine alone: one could only love the USSR, the party and "the great leaders." The poem remained in Ukrainian school textbooks in this editorial version until the early 2000s.

“Yalovy’s arrest is the execution of the entire Generation…”

The funeral of Mykola Khvylovy, Kharkiv, May, 1933 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

The funeral of Mykola Khvylovy, Kharkiv, May, 1933 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)This is the first line of the suicide note written by Mykola Khvylovy, the leader of the 1920s generation in literature. He shot himself in his apartment in the Word Building in Kharkiv on May 13, 1933. In a couple of years, the generation of the 1920s artists will be executed quite literally.

For the Bolshevik regime, that was a very efficient method to get rid of new works and meanings that failed to comply with the official doctrine or were outright hostile to it, resisting the socialist realist canon with its glorification of the Soviet regime.

All that was left was to handle the existing “antitexts.” Literature, after all, had to serve just one function: that of propaganda.

The Main Directorate for Literature and Publishing Houses issued lists of banned literature that were used to remove works of repressed writers from libraries and book depositories. The first lists were very detailed, including the author’s surname, the title of the work, the publishing house, the year of publication and language. As repressions intensified after the mid-1930s, censors had to leave out details because of the scope of the task at hand, making do with the formula “all works from all years in any language.” Removing publications based on these lists decimated the Ukrainian book depositories.

In the coming decades, mass executions of artists were replaced with long prison terms and forced commitment to psychiatric wards, but the goal remained unchanged: to make impossible authentic expressions of Ukrainian national culture.

Phantom Texts

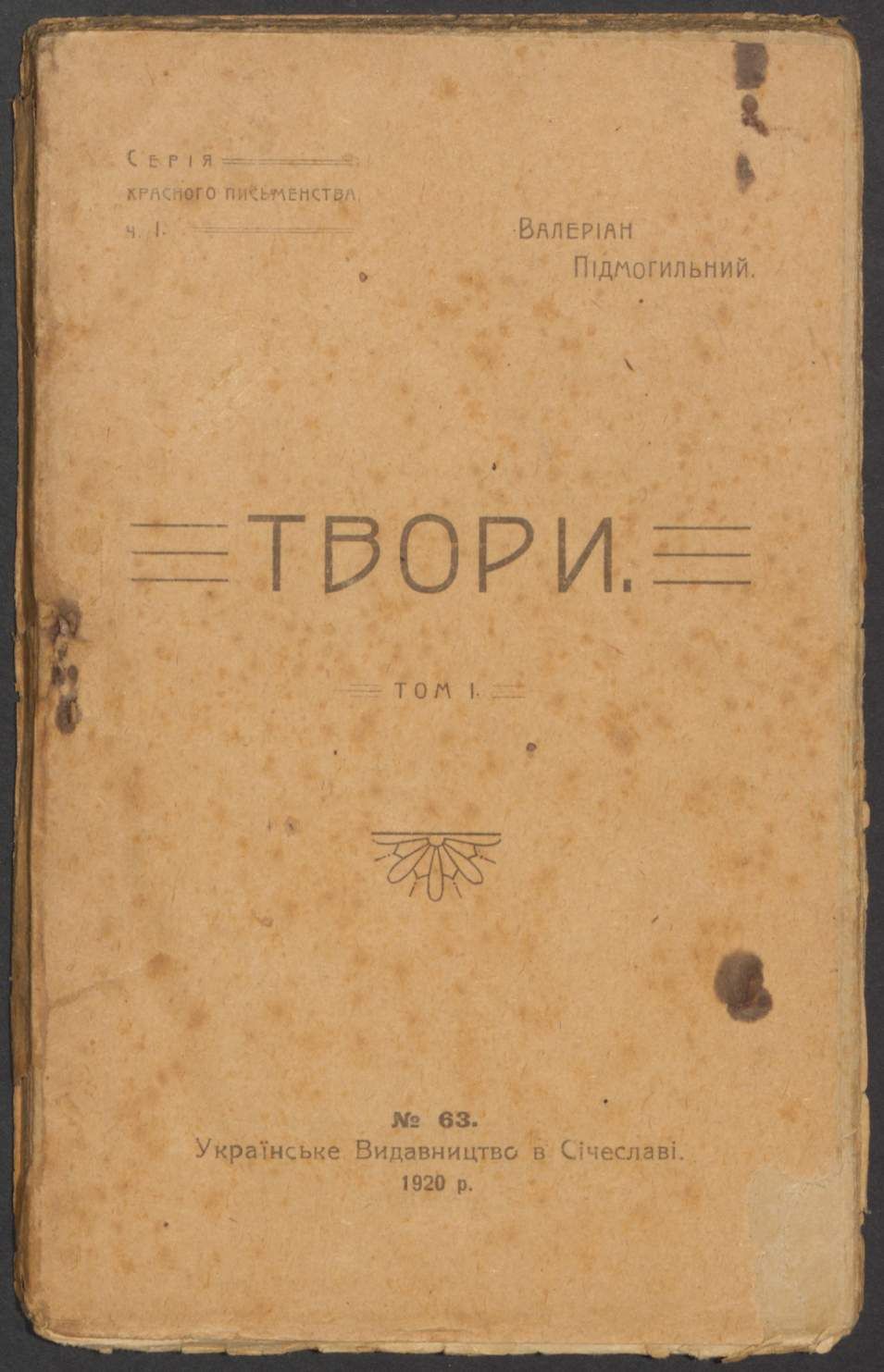

Valeriian Pidmohylny. Works. Ukrainian Publishing in Sicheslav, 1920 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Valeriian Pidmohylny. Works. Ukrainian Publishing in Sicheslav, 1920 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)“From day one, ever since I arrived here, I had the burning desire, the real need to write about collectivization. It found scant reflection in Ukrainian literature. But the moment I started thinking about this topic, I faced the difficulties of such a colossal scale that I abandoned the idea altogether. And then, very recently, the idea formed in my mind. I began writing, and it seems it’s not bad,” wrote the Ukrainian writer and translator Valeriian Pidmohylny in a letter to his wife from April 12, 1936, about his new novel Autumn 1929. He was arrested on false charges of planning terror attacks against the leaders of the Bolshevik party, and was serving his sentence on Solovki. In three months, he completed 6 out of 12 planned chapters. In other letters, he also mentioned working on a novella entitled Natasha and Masha, translating Shakespeare’s Henry VI and Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray.

All these texts were doomed to stay in Solovki forever, and only the most inveterate romantics still dream of rediscovering them one day. Never having been published, these manuscripts are believed to be lost. The same is true for the works of other artists confiscated during their arrests and searches or written in prison. Every trace is lost.

* The Experience of Love and the Critique of Pure Reason. Valeriian Pidmohylny: Texts and the Conflict of Interpretations [Досвід кохання і критика чистого розуму. Валер'ян Підмогильний: тексти та конфлікт інтерпретацій], Kyiv, 2003. Edited by Olena Haleta.

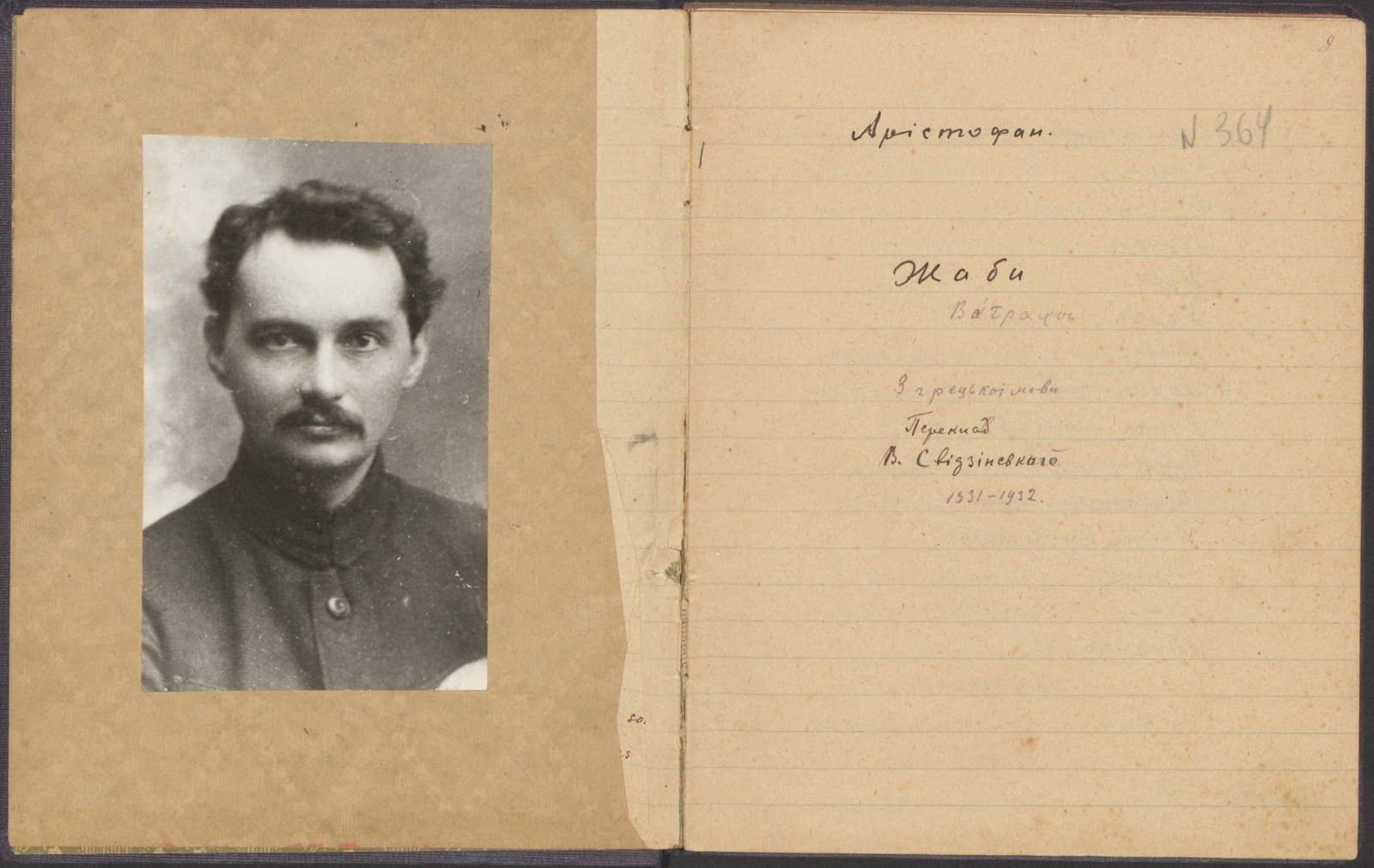

Volodymyr Svidzynsky. Manuscript of the translation of Aristophanes, 1931 - 1932 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Volodymyr Svidzynsky. Manuscript of the translation of Aristophanes, 1931 - 1932 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)In the early 1930s, the Ukrainian poet, translator and literary historian Mykola Zerov began translating Virgil’s Aeneid. The parts that he managed to complete before his arrest in 1935 weren’t published until 1966, when the poet Maksym Rylsky finally managed to get them in print. Zerov continued the translation during his prison sentence in Solovki. The texts were never found.

Volodymyr Svidzynsky, a poet of the Executed Renaissance generation, was arrested by the NKVD in Kharkiv in 1941, as the German army was approaching the city. In the autumn of that same year, he and other prisoners were burned alive in a barn during the first stage of their evacuation to the east. The manuscripts of unpublished poems were burned with the poet. His works would have been forgotten if not for his friend Oleksa Veretenchenko, himself a writer, who managed to take a manuscript of Svidzynsky’s poems, edited by the author, into emigration during the tumultuous days of WW II.

Mykola Kulish. Manuskript about the history of VKP(b) - The All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, early 1930s. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Mykola Kulish. Manuskript about the history of VKP(b) - The All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, early 1930s. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)A manuscript of the play Like This by Mykola Kulish, the most famous playwright of the 1920s-30s, was confiscated by the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR during a search after the writer’s arrest in 1934. The manuscript never resurfaced again.

Manuscripts by the short story writer Hryhorii Kosynka (“A Red Bug,” “Binding Straw String”), confiscated during his arrest in 1934, were never found. “We are looking for you in every dewdrop,” the writer Andrii Malyshko wrote about him in 1956.

The full text of the long poem Germany by the Futurist poet Mykhail Semenko, confiscated during his arrest in 1937, was never found. The poet had only published excerpts from it.

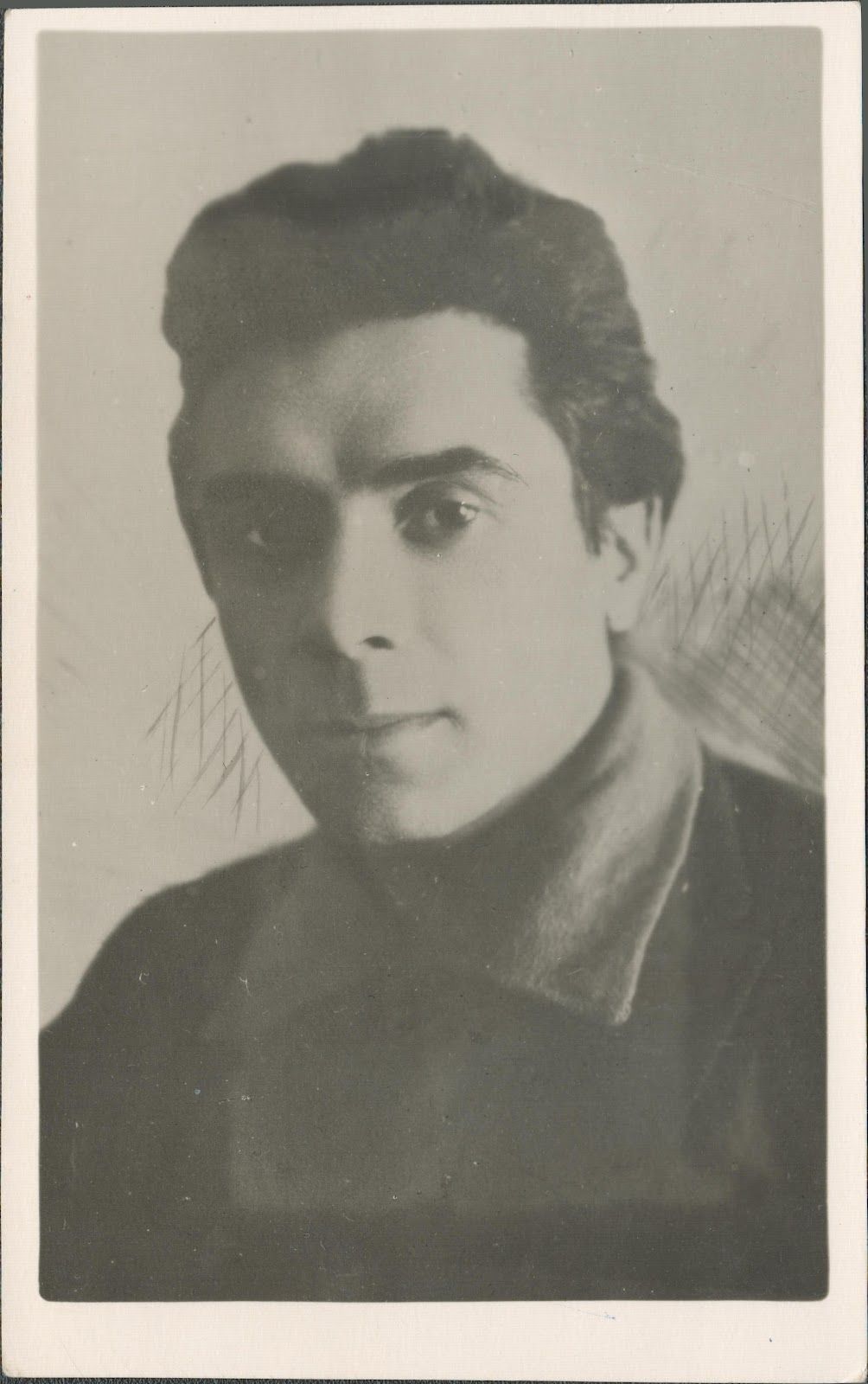

Mykola Khvylovy, 1929. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Mykola Khvylovy, 1929. (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)Mykola Khvylovy (1893–1933) was a Ukrainian prose writer, essayist and poet of the 1920s–1930s, politically a national communist. Most of his pamphlets are a striking mixture of the national question and the communist ideology. The communist Khvylovy advocated the independent development of the Ukrainian culture and argued that it should not embrace the Russian culture as its model. Are we ready to acknowledge this combination in Khvylovy's beliefs? After all, describing him as just a communist or just as a champion of the national culture means engaging in censorship, especially given that the current reader has both the right and the opportunity to read his "unbowdlerized" works.

The Burned Manuscript

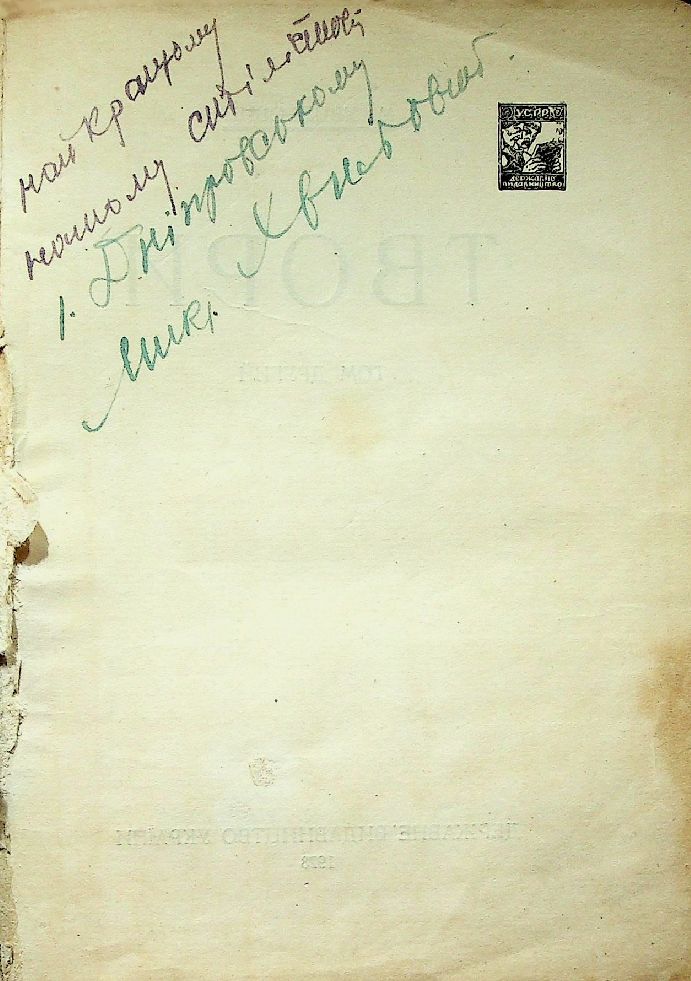

Mykola Khvylovy’s book with his autograph for Ivan Dniprovky (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Mykola Khvylovy’s book with his autograph for Ivan Dniprovky (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)Mykola Khvylovy’s novel Woodcocks was written at the height of the 1925-28 literary discussion, a public debate around the challenges and the development of Ukrainian Soviet literature. The discussion was prompted by Khvylovy’s polemical essays in Ukrainian press. Since the discussion unfolded right as the Bolshevik party was instilling ever stronger control over cultural processes and curtailed pro-Ukrainian affirmative policies, it turned political very soon. The authorities used it as a pretext to level ideological accusations against Khvylovy for advocating the development of Ukrainian literature that would be independent of Russia and orientated towards “the psychological Europe,” and for rejecting the need for mass production.

Part 1 of Khvyliovy’s Woodcocks had been published in Issue 5 of the bi-monthly magazine VAPLITE, named after the eponymous literary organization. Part 2 was to be published in Issue 6. The censorship confiscated the already printed issue on January 28, 1928; not a single surviving copy has been found to date.

Under political pressure, Khvylovy publically repented and destroyed the novel’s manuscript. The text allegedly survived as typographical forms; there are memoirs of Ukrainian artists and scholars who managed to have read it. But the text of the lost part of the novel was never recreated.

“I hereby inform my literary associates that I have destroyed the ending of my novel Woodcocks, and, having destroyed it, my every thought goes to wiping away, at least in part, the stain on my name as a party man and a writer.” (Mykola Khvylovy’s letter to the Communist newspaper, February 22, 1928, Central State Archive/Museum of Art and Literature of Ukraine)

Ukrainians outside scholarship

After the mid-1930s, the vast majority of Ukrainian ethnographers have been repressed, and institutes of ethnography were liquidated. They were not reestablished until after WW II. In the early 1950s, a request came from Moscow for a chapter on Ukrainians for the volume of Nations of the European Part of the USSR, to be published in Russian in the “Nations of the World” series. The leadership of the Institute of Art Scholarship, Folklore and Ethnography of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, or Maksym Rylsky and Kost Huslysty, to be more precise, grasped at the opportunity to suggest that a longer Ukrainian-language edition could be prepared. That launched a large-scale research project, which included ethnological expeditions around Ukraine.

The monograph Ukrainians was to encompass two volumes: the first focusing on “the culture and daily life of the Ukrainian people in the late 19th-the early 20th century,” while the 2nd moved on to the “Socialist transformations after the Great October Socialist Revolution.” An updated version of Volume 1, integrating revisions and notes made during discussions, was prepared in 1960.

Nevertheless, all mentions of the monograph Ukrainians soon disappeared from the pages of specialized periodicals. Volume 1 only existed in proofs, accessible to the small cohort of researchers. The project was cut short because it did not comply with the dominant ideology. The research materials pointed to the unique history and culture of Ukrainians, which ran counter to the ideology of the “united Soviet nation.”

“But books and facts linger in archives like dynamite.” (Yevhen Sverstiuk, “On the trial of Pohruzhalsky” [З приводу процесу над Погружальським], Suchasnist, February 1965).

On May 24, 1964, a fire broke out in the State Public Library of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR. It took 31 hours to put out the fire. Approximately 500,000 items in the library’s holdings were destroyed, with the collection partially replenished with extra copies.

A library worker Viktor Pohruzhalsky was accused of arson. Both the figure of the accused (the trial blatantly prioritized the version of Pohruzhalsky’s antipathy for and revenge against the library director) and the secrecy surrounding the case (including which library departments suffered the heaviest losses) produced a version that arson at the research library was a special action organized and planned by the Soviet secret services to destroy Ukrainian cultural heritage.

Yevhen Sverstiuk with his son, Кyiv, 1970 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Yevhen Sverstiuk with his son, Кyiv, 1970 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)Yevhen Sverstiuk, a Ukrainian literary critic and a political prisoner of the Soviet regime, wrote a pamphlet “On the trial of Pohruzhalsky” right after the event. He noted that the Ukrainian Studies department, storing precious publications, old books and manuscripts from the field of Ukrainian history and culture, suffered the heaviest losses. A large part of manuscripts destroyed in the fire have never been published, so the public could not even evaluate the scope of what had been lost. That highlighted the general disregard for Ukrainian cultural heritage. Sverstiuk’s essay existed in self-published versions; copying, keeping or disseminating it could lead to an arrest and a prison sentence.

“Therefore, a part of the Ukrainian history, a part of the Ukrainian culture were destroyed in the fire. Immense spiritual treasures were lost forever. Thousands and millions of people, whole new generations are blocked from accessing many spiritual sources, books and documents. Some are lost forever while others may still linger in copies, if inaccessible to the reader.”

(Yevhen Sverstiuk, “On the trial of Pohruzhalsky” [З приводу процесу над Погружальським], Suchasnist, February 1965).

A Caged Bird

Valer Bondar's drawing for the poem from Palimpsests by Vasyl Stus, Kharkiv, 1988 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)

Valer Bondar's drawing for the poem from Palimpsests by Vasyl Stus, Kharkiv, 1988 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection)The poet Vasyl Stus spent 12 years out of his 47-year life in jail for “anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” No more than a couple of months had passed between his first release in 1979 and his second arrest in 1980. The camps are no place for poetry, but he never gave up writing.

Manuscripts were confiscated whenever his cell was searched. Stus would recreate his poems from memory, and his camp “colleagues” would then copy and memorize them. This explains the multitude of versions/variations of each poem.

This also explains why his collection Palimpsests exists in two versions: the shorter “Magadan version” with poems from his first imprisonment, and the “Kyiv version” that the poet didn’t have the time to edit to completion before his second arrest. One draft was smuggled out of the USSR and published in New York in 1986, with George Shevelov as its editor. Before that, Nadia Svitlychna had spent several years deciphering the manuscript.

The Lithuanian couple, Balys Gajauskas and Irena Gajauskienė, had also managed to secretly deliver the text of his From the Camp Notebook to freedom.

During his second prison term, Vasyl Stus jotted down poems for his eventual collection The Bird of My Soul, which was to include his blank verse and translations (including Rilke’s poems), in a school notebook. The notebook was confiscated after a search of his cell, and the poet failed to receive it back. In all likelihood, The Bird of My Soul was destroyed.

Vasyl Stus Christmas celebration in Lviv, 1972 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection).

Vasyl Stus Christmas celebration in Lviv, 1972 (Kharkiv Literary Museum’s collection).Rewritten by the poet, circulated in samizdat and confiscated during searches in the camps where the poet was imprisoned for anti-Soviet propaganda, some poems by Vasyl Stus (1938–1985) now exist in many variants. With the exception of a few newspaper publications, Vasyl Stus wasn't published during his lifetime. Soviet censorship banned him from publication, so there are not that many works that were published while the poet was still alive. As a result, researchers are now dealing with variant readings, while a part of his legacy is lost forever. Overlaying two variants of a single poem, we create a visual effect of "illegibility." Persecuted by the Soviet communist regime, Vasyl Stus remains not fully discovered to this day.